Back in November, Rishi Sunak commented on Radio 4’s Today programme that the current projections for UK borrowing are “obviously not sustainable”. The question that nobody seems prepared to put to him is why there is no attempt made to balance the books? It’s as if the consensus on the need to spend and the knowledge that borrowing is cheap means that the normal expectations of raising taxes to pay short-term costs no longer apply. The only people who vociferously question the wisdom of this just want us to plough on through the pandemic without imposing lockdown measures, believe economic ills can be avoided this way and that they can justify the consequential deaths and health-service meltdown as the lesser of two evils.

But whilst we all understand that the normal rules may be broken in extraordinary times, does acting in an economically unsustainable way actually reduce or compound the problem?

Because it’s one thing to commit to a known amount of borrowing and another to commit to writing any number of cheques to get us through and worry about how they are going to be honoured later.

And then, pressured by recognition of the gambles he is taking, he thinks that he can take the edge off by doing the same but just a bit less i.e not writing all of the cheques necessary, or else capping them. For his other repeated mantra that few have looked to challenge is that he “can’t support everyone”. Which, of course, is not true: he’s the Chancellor; if there’s a will there’s a way.

Those who are not supported or not supported sufficiently well are then written off as “nonviable”. And they will be considered, even sometimes by the people themselves, as victims of the pandemic. They are not. Furlough payments and support grants are not really acts of beneficence: they are compensation payments for the Government’s messing with the normal social contract that the Government has a moral duty to honour.

And whilst we’ve yet to find out who will pay for this, we’ve had a foretaste in his recent spending review. The bulk of public sector workers are to have a pay freeze even though many of their number have been at the forefront of our battle against the virus and sustained casualties in doing so.

In October, I performed some rudimentary modelling to look into what it would cost to provide comprehensive life support for all businesses affected by the Government’s public health restrictions. There is plenty of scope to quibble with the figures here, but it alarms me that I’m struggling to find anyone else motivated to do something similar and publish their findings.

Cutting to the headlines, I reckoned on the figure of £240 billion per annum to provide proper sustainable support to tie businesses and their employees through the most stringent of lockdowns. This could be paid for by raising income tax by 26p and corporation tax by 21p. Now, so long as the Chancellor does not shirk his responsibility for paying in full to keep businesses afloat, I’m not adamantly opposed to him failing to raise taxes now. And there will be many who will blanche at these figures and believe that it’s not politically possible to levy supplements anywhere near these levels even over the short term. But the Chancellor’s been giving strong hints that collection day is on its way. And I think we need to look at whether the alternatives will be any better.

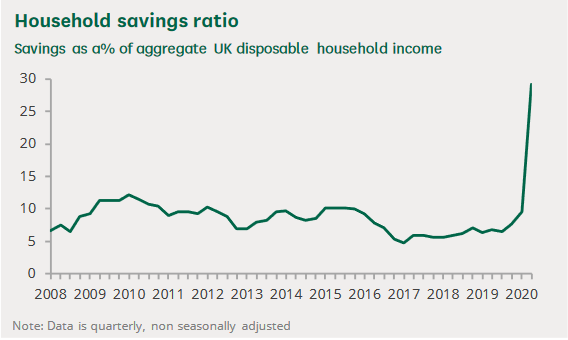

I began this train of thought by pointing out that the money to pay these kinds of bills must logically be available because it was not being spent. This has now been confirmed by the ONS who reckon that the percentage of disposable income directed towards savings trebled to reach 29.1% in the 2nd quarter of this year, an all-time high since records began in 1987. This was driven by an £80.5 billion reduction in spending in the quarter.

The problem is that whilst the top 4 of the 5 earning quintiles saved more between March and September 2020 than they did in the corresponding period in 2019, the lowest quintile saved less. This indicates that the poorest are bearing the heaviest burden of the pandemic, and this is a conclusion shared by the ONS.

The unconscionable thing, though, is that whilst the poor are hit hardest, public sector workers have been earmarked for austerity and businesses and individuals driven to bankruptcy, there are many in the UK who are richer at the end of this pandemic period than they were at the beginning. And yet they’ve not been asked to pay a penny piece more in tax[1].

[1] (1) Figures taken from House of Commons Briefing Paper, Author: Bridgid Francis-Devine (26th November 2020). https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/CBP-9060/CBP-9060.pdf